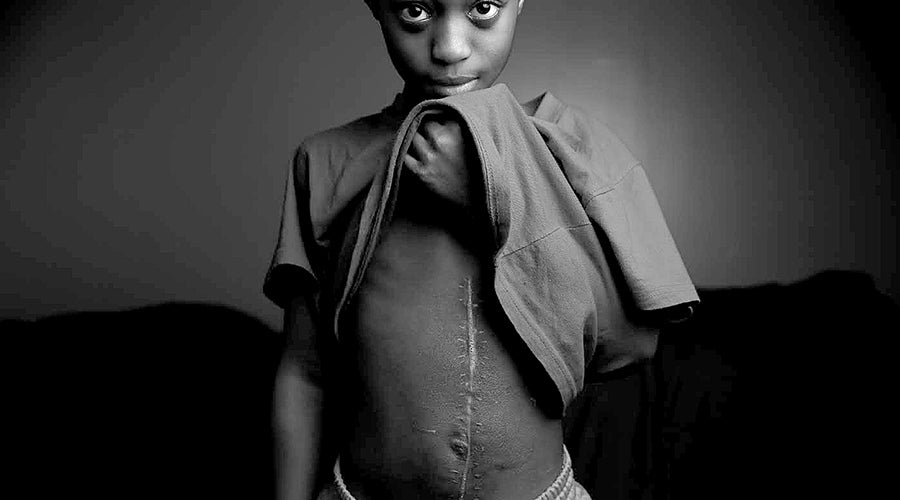

- Tavon Tanner, 11, was shot on his West Polk Street porch in August, with his mother Mellanie Washington next to him. He was in the hospital until late September, the result of the initial surgery followed by infection. Photographed, Oct. 14, 2016. (E. Jason Wambsgans / Chicago Tribune)

Former Niles Daily Star photographer wins Pulitzer Prize

Published 1:13 pm Monday, April 24, 2017

On April 10, Jason Wambsgans spent his evening celebrating and reflecting on his career after earning perhaps the highest recognition that can be bestowed upon a photographer.

The Chicago Tribune photojournalist added a Pulitzer Prize to his long list of achievements. This particular accolade was awarded for the work Wambsgans did to illustrate a 10-year-old Chicago boy’s journey after being shot. The series that earned the Pulitzer for feature photography captures the life of Tavon Tanner, an “unintended target” like so many other victims of violence in the Windy City.

The Chicago Tribune photojournalist added a Pulitzer Prize to his long list of achievements. This particular accolade was awarded for the work Wambsgans did to illustrate a 10-year-old Chicago boy’s journey after being shot. The series that earned the Pulitzer for feature photography captures the life of Tavon Tanner, an “unintended target” like so many other victims of violence in the Windy City.

Before he made it to the big time, Wambsgans cut his teeth working the photo beat for the Niles Daily Star. In an interview Wednesday, Wambsgans remembered his early career with the Star and how it helped to shape him as an award-winning photographer.

Baptism by fire

Standing in the Niles post office, a novice photographer clutches a camera in clammy hands.

As patrons go about their business, he eyes them nervously, pondering who would be easiest to approach.

Every interaction involves a summoning of courage, but Wambsgans said he knew he could not face the newsroom at the Niles Daily Star without at least 10 photographs and answers for the “Question of the Week.”

The assignment was the doing of then Niles Daily Star Editor Jan Griffey, determined to help the rookie photographer overcome his shyness.

That was in 1995 — and it is a far cry from the day-to-day duties of the seasoned Chicago Tribune photojournalist, who at times has had to strap on a Kevlar vest to cover murders in the pre-dawn hours. In the time since walking the streets of Niles with his eye behind the shutter, Wambsgans has tread miles of foreign territory to capture the faces to spread a message, such as people war-torn in Afghanistan.

Still, he remembers shooting pictures of the Apple Festival and Berrien County Fair.

Informal training

“I was always playing with cameras when I was a kid,” Wambsgans said.

Growing up in Trenton, Michigan — a city 25 miles outside of Detroit — it was not uncommon for Wambsgans and his mother to drive around exploring the city. Such explorations were an opportunity to capture what young Wambsgans saw.

“I always visually loved the way Detroit looked. [The] architecture, not just the crumbling parts of it, the beautiful parts, [too].”

Wambsgans also loved drawing and making visual art.

Wambsgans attended Central Michigan University, where he pursued his interest in filmmaking and art. At the time, Wambsgans said he had little interest in pursuing a career in journalism, until a few friends recommended that he join the student newspaper. They told him he would get paid to shoot photos. The school newsroom also had a much nicer dark room than the art department, Wambsgans was sold.

Then, in a photo history class, Wambsgans saw how capturing photos for a newspaper could be art.

“There were certain photographers that I was really drawn to, where it was journalism, but it also struck me as being art, but it was based in the reality of people’s lives,” Wambsgans said. “That kind of opened the idea that that might be something I was interested in.”

An advisor at a paper pushed Wambsgans to apply for two open positions as a photojournalist. One of the positions was for a newspaper in Gross Clinton, Michigan. The other was for a newspaper in Niles.

Wambsgans arranged his portfolio, which he said consisted of a couple of rock band photographs and a portrait of his dad.

“It was a terrible portfolio,” Wambsgans said. “It was preposterous.”

Wambsgans visited Niles for an interview with Griffey and got the job.

“She was fine with the idea that I had never had a journalism class and I had all these goofy ideas about art in my head,” Wambsgans said. “And they gave me a chance.”

Serving the Star

Through two years taking photos for the Niles Daily Star, Wambsgans chronicled traditions like the Apple Festival, Blossomtime Scholarship Pageant and Berrien County Fair, winning the praise of not only his editor, but also the community.

But when Wambsgans first took over the beat, he said there was a lot he had to learn.

“Right away it was a little bit of culture shock,” Wambsgans said.

The photographer was also so shy that the first couple of weeks on the job, he said, he took pictures of people only from the back so that he would not have to ask their names.

But Wambsgans was determined.

Tasked with talking to people every day to pursue his passion for photography, the young journalist saw an opportunity to grow in his career.

Between working 12- to 15-hour work days and spending weekends poring over photography books at Barnes and Nobles in Mishawaka, Wambsgans said he did all he could to absorb tips for the job.

New to southwest Michigan, Wambsgans got to experience community traditions with a fresh set of eyes.

“It was exhilarating to see everything for the first time,” he said.

Each week, Wambsgans published a photo essay, filling an entire open page with pictures of what was happening around town.

“It was extremely rare to have that opportunity to have that much real estate to tell stories visually,” Wambsgans said. “That was really a chance to grow as a photojournalist.”

Whether the photos were good or bad, Wambsgans was certain to hear about it.

“It was instant feedback,” Wambsgans said. “It was really wonderful. I really felt like I was embraced by the community. People would send me letters every day and say ‘your pictures are getting better.’”

Looking back on those early years, Wambsgans credits experiences like a Horizons photo project, where he captured Niles over 24 hours, as helping him to develop a signature style.

“For me and my development it was the beginning of a distinct part of my style and aesthetic as a photojournalist,” Wambsgans said.

Niles funeral director Jim Myer recalls one particular spread where Wambsgans cataloged 24 hours in the city of Four Flags, beginning the day with a birth at the local hospital and ending it with photos of a deceased person being carried into Halbritter Funeral Home.

The photos showed not just Niles, but the people who make the city what it was.

Winning the Pulitzer

Two decades later, Wambsgans still spends his days with a camera strapped around his neck. A short drive west from Niles, the photographer now tells visual stories of Chicagoans, like the one featured in his Pulitzer-Prize-winning project.

The project evolved from four years of working a photo crime beat and chronicling the violence that took lives and left a wake of fear on Chicago’s city streets.

Locating someone who was willing to be open about his or her child being an “unintended target” of gun violence proved difficult.

Then Wamsbgans met Tavon Tanner and his mother Mellanie Washington, who wanted their story told.

In a black and white photograph, 10-year-old Tavon stares casually into the camera as he lifts his shirt to reveal a scar that stretches across his stomach.

The photos accompanied the story, “Tavon Tanner, a bullet, and what happened on the streets of Chicago” was written by journalist Mary Schmich. Together Wambsgans and Smich tell the story of a Tavon, who was one of 24 “unintentional targets” of gun violence last year.

Though Tavon survived the shooting on Aug. 8, 2016, a surgery and attempts to help the child recover psychological ramifications of the shooting followed.

Through Wambsgans’ photos, readers can see how this life-changing event impacted the young boy.

Wambsgans hung out with Tavon and his family — playing catch with Tavon, spending Thanksgiving with his relatives, hoping to get to know them and help them feel comfortable as he chronicled their story.

“This is the best case when the photographs in the story intertwine together to tell a story in different ways, so they both become more powerful,” Wambsgans said. “People in other parts of the city and country where this does not happen, they can see a glimpse of this family and be in their shoes.”

In this case, Wambsgans said a hardworking mother did everything she could to protect her children, even forbidding them to play in the front yard, but as the story shows, in Chicago there are elements out of a mother’s control.

“To be able to hopefully give people a glimpse of someone else’s life and put them in their shoes and create some kind of understanding between different people who might not actually ever meet in real life, that is the best thing you can do with photography,” Wambsgans said.

By Kelsey Hammon / Leader Publications